Quartz

| Quartz | |

|---|---|

Quartz crystal cluster from Brazil | |

| General | |

| Category | Silicate mineral[1] |

| Formula (repeating unit) | SiO2 |

| IMA symbol | Qz[2] |

| Strunz classification | 4.DA.05 (oxides) |

| Dana classification | 75.01.03.01 (tectosilicates) |

| Crystal system | α-quartz: trigonal β-quartz: hexagonal |

| Crystal class | α-quartz: trapezohedral (class 3 2) β-quartz: trapezohedral (class 6 2 2)[3] |

| Space group | α-quartz: P3221 (no. 154)[4] β-quartz: P6222 (no. 180) or P6422 (no. 181)[5] |

| Unit cell | a = 4.9133 Å, c = 5.4053 Å; Z = 3 |

| Identification | |

| Formula mass | 60.083 g·mol−1 |

| Color | Colorless, pink, orange, white, green, yellow, blue, purple, dark brown, or black |

| Crystal habit | 6-sided prism ending in 6-sided pyramid (typical), drusy, fine-grained to microcrystalline, massive |

| Twinning | Common Dauphine law, Brazil law, and Japan law |

| Cleavage | {0110} Indistinct |

| Fracture | Conchoidal |

| Tenacity | Brittle |

| Mohs scale hardness | 7 – lower in impure varieties (defining mineral) |

| Luster | Vitreous – waxy to dull when massive |

| Streak | White |

| Diaphaneity | Transparent to nearly opaque |

| Specific gravity | 2.65; variable 2.59–2.63 in impure varieties |

| Optical properties | Uniaxial (+) |

| Refractive index | nω = 1.543–1.545 nε = 1.552–1.554 |

| Birefringence | +0.009 (B-G interval) |

| Pleochroism | None |

| Melting point | 1670 °C (β tridymite); 1713 °C (β cristobalite)[3] |

| Solubility | Insoluble at STP; 1 ppmmass at 400 °C and 500 lb/in2 to 2600 ppmmass at 500 °C and 1500 lb/in2[3] |

| Other characteristics | Lattice: hexagonal, piezoelectric, may be triboluminescent, chiral (hence optically active if not racemic) |

| References | [6][7][8][9] |

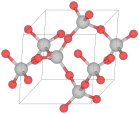

Quartz is a hard, crystalline mineral composed of silica (silicon dioxide). The atoms are linked in a continuous framework of SiO4 silicon–oxygen tetrahedra, with each oxygen being shared between two tetrahedra, giving an overall chemical formula of SiO2. Quartz is, therefore, classified structurally as a framework silicate mineral and compositionally as an oxide mineral. Quartz is the second most abundant mineral in Earth's continental crust, behind feldspar.[10]

Quartz exists in two forms, the normal α-quartz and the high-temperature β-quartz, both of which are chiral. The transformation from α-quartz to β-quartz takes place abruptly at 573 °C (846 K; 1,063 °F). Since the transformation is accompanied by a significant change in volume, it can easily induce microfracturing of ceramics or rocks passing through this temperature threshold.

There are many different varieties of quartz, several of which are classified as gemstones. Since antiquity, varieties of quartz have been the most commonly used minerals in the making of jewelry and hardstone carvings, especially in Europe and Asia.

Quartz is the mineral defining the value of 7 on the Mohs scale of hardness, a qualitative scratch method for determining the hardness of a material to abrasion.

Etymology

[edit]The word "quartz" is derived from the German word Quarz,[11] which had the same form in the first half of the 14th century in Middle High German and in East Central German[12] and which came from the Polish dialect term twardy, which corresponds to the Czech term tvrdý ("hard").[13] Some sources, however, attribute the word's origin to the Saxon word Querkluftertz, meaning cross-vein ore.[14][15]

The Ancient Greeks referred to quartz as κρύσταλλος (krustallos) derived from the Ancient Greek κρύος (kruos) meaning "icy cold", because some philosophers (including Theophrastus) understood the mineral to be a form of supercooled ice.[16] Today, the term rock crystal is sometimes used as an alternative name for transparent coarsely crystalline quartz.[17][18]

Early studies

[edit]Roman naturalist Pliny the Elder believed quartz to be water ice, permanently frozen after great lengths of time.[19] He supported this idea by saying that quartz is found near glaciers in the Alps, but not on volcanic mountains, and that large quartz crystals were fashioned into spheres to cool the hands. This idea persisted until at least the 17th century. He also knew of the ability of quartz to split light into a spectrum.[20]

In the 17th century, Nicolas Steno's study of quartz paved the way for modern crystallography. He discovered that regardless of a quartz crystal's size or shape, its long prism faces always joined at a perfect 60° angle thus discovering the law of constancy of interfacial angles.[21]

Crystal habit and structure

[edit]Quartz belongs to the trigonal crystal system at room temperature, and to the hexagonal crystal system above 573 °C (846 K; 1,063 °F). The ideal crystal shape is a six-sided prism terminating with six-sided pyramid-like rhombohedrons at each end. In nature, quartz crystals are often twinned (with twin right-handed and left-handed quartz crystals), distorted, or so intergrown with adjacent crystals of quartz or other minerals as to only show part of this shape, or to lack obvious crystal faces altogether and appear massive.[22][23]

Well-formed crystals typically form as a druse (a layer of crystals lining a void), of which quartz geodes are particularly fine examples.[24] The crystals are attached at one end to the enclosing rock, and only one termination pyramid is present. However, doubly terminated crystals do occur where they develop freely without attachment, for instance, within gypsum.[25]

α-quartz crystallizes in the trigonal crystal system, space group P3121 or P3221 (space group 152 or 154 resp.) depending on the chirality. Above 573 °C (846 K; 1,063 °F), α-quartz in P3121 becomes the more symmetric hexagonal P6422 (space group 181), and α-quartz in P3221 goes to space group P6222 (no. 180).[26]

These space groups are truly chiral (they each belong to the 11 enantiomorphous pairs). Both α-quartz and β-quartz are examples of chiral crystal structures composed of achiral building blocks (SiO4 tetrahedra in the present case). The transformation between α- and β-quartz only involves a comparatively minor rotation of the tetrahedra with respect to one another, without a change in the way they are linked.[22][27] However, there is a significant change in volume during this transition,[28] and this can result in significant microfracturing in ceramics during firing,[29] in ornamental stone after a fire[30] and in rocks of the Earth's crust exposed to high temperatures,[31] thereby damaging materials containing quartz and degrading their physical and mechanical properties.

-

Common, prismatic quartz

-

Sceptered quartz

-

Sceptered quartz (as aggregates: "Elestial quartz")

-

Bipyramidal quartz

-

Tessin or tapered quartz

-

Twinned quartz (known as Japan law)

-

Dauphine quartz (single dominant face)

-

Druse quartz

-

Granular quartz

-

Massive quartz

Varieties (according to microstructure)

[edit]Although many of the varietal names historically arose from the color of the mineral, current scientific naming schemes refer primarily to the microstructure of the mineral. Color is a secondary identifier for the cryptocrystalline minerals, although it is a primary identifier for the macrocrystalline varieties.[32]

The most important microstructure difference between types of quartz is that of macrocrystalline quartz (individual crystals visible to the unaided eye) and the microcrystalline or cryptocrystalline varieties (aggregates of crystals visible only under high magnification). The cryptocrystalline varieties are either translucent or mostly opaque, while the macrocrystalline varieties tend to be more transparent. Chalcedony is a cryptocrystalline form of silica consisting of fine intergrowths of both quartz, and its monoclinic polymorph moganite.[33] Agate is a variety of chalcedony that is fibrous and distinctly banded with either concentric or horizontal bands.[34] While most agates are translucent, onyx is a variety of agate that is more opaque, featuring monochromatic bands that are typically black and white.[35] Carnelian or sard is a red-orange, translucent variety of chalcedony. Jasper is an opaque chert or impure chalcedony.[36]

| Type | Color and description | Transparency | Microstructure |

|---|---|---|---|

| Herkimer diamond | Colorless | Transparent | Macrocrystalline |

| Rock crystal | Colorless | Transparent | Macrocrystalline |

| Amethyst | Purple to violet colored quartz | Transparent | Macrocrystalline |

| Citrine | Yellow quartz ranging to reddish-orange or brown (Madeira citrine), and occasionally greenish yellow | Transparent | Macrocrystalline |

| Rose quartz | Pink, may display diasterism | Transparent | Macrocrystalline |

| Chalcedony | Fibrous, occurs in many varieties. The term is often used for white, cloudy, or lightly colored material intergrown with moganite. Otherwise more specific names are used. |

Translucent to opaque | Cryptocrystalline |

| Carnelian | Reddish orange chalcedony | Translucent | Cryptocrystalline |

| Aventurine | Quartz with tiny aligned inclusions (usually mica) that shimmer with aventurescence | Translucent to opaque | Macrocrystalline |

| Agate | Multi-colored, concentric or horizontal banded chalcedony | Semi-translucent to translucent | Cryptocrystalline |

| Onyx | Typically black-and-white-banded or monochromatic agate | Semi-translucent to opaque | Cryptocrystalline |

| Jasper | Impure chalcedony or chert, typically red to brown but the name is often used for other colors | Opaque | Cryptocrystalline or Microcrystalline |

| Milky quartz | White, may display diasterism | Translucent to opaque | Macrocrystalline |

| Smoky quartz | Light to dark gray, sometimes with a brownish hue | Translucent to opaque | Macrocrystalline |

| Tiger's eye | Fibrous gold, red-brown or bluish colored chalcedony, exhibiting chatoyancy. | Opaque | Cryptocrystalline |

| Prasiolite | Green | Transparent | Macrocrystalline |

| Rutilated quartz | Contains acicular (needle-like) inclusions of rutile | Transparent to translucent | Macrocrystalline |

| Dumortierite quartz | Contains large amounts of blue dumortierite crystals | Translucent | Macrocrystalline |

Varieties (according to color)

[edit]

Pure quartz, traditionally called rock crystal or clear quartz, is colorless and transparent or translucent and has often been used for hardstone carvings, such as the Lothair Crystal. Common colored varieties include citrine, rose quartz, amethyst, smoky quartz, milky quartz, and others.[37] These color differentiations arise from the presence of impurities which change the molecular orbitals, causing some electronic transitions to take place in the visible spectrum causing colors.

Amethyst

[edit]Amethyst is a form of quartz that ranges from a bright vivid violet to a dark or dull lavender shade. The world's largest deposits of amethysts can be found in Brazil, Mexico, Uruguay, Russia, France, Namibia, and Morocco. Amethyst derives its color from traces of iron in its structure.[38]

Ametrine

[edit]Ametrine, as its name suggests, is commonly believed to be a combination of citrine and amethyst in the same crystal; however, this may not be technically correct. Like amethyst, the yellow quartz component of ametrine is colored by iron oxide inclusions. Some, but not all, sources define citrine solely as quartz with its color originating from aluminum-based color centers.[39][40] Other sources do not make this distinction.[41] In the former case, the yellow quartz in ametrine is not considered true citrine. Regardless, most ametrine on the market is in fact partially heat- or radiation-treated amethyst.[41]

Blue quartz

[edit]Blue quartz contains inclusions of fibrous magnesio-riebeckite or crocidolite.[42]

Dumortierite quartz

[edit]Inclusions of the mineral dumortierite within quartz pieces often result in silky-appearing splotches with a blue hue. Shades of purple or gray sometimes also are present. "Dumortierite quartz" (sometimes called "blue quartz") will sometimes feature contrasting light and dark color zones across the material.[43][44] "Blue quartz" is a minor gemstone.[43][45]

Citrine

[edit]Citrine is a variety of quartz whose color ranges from yellow to yellow-orange or yellow-green. The cause of its color is not well agreed upon. Evidence suggests the color of citrine is linked to the presence of aluminum-based color centers in its crystal structure, similar to those of smoky quartz. Both smoky quartz and citrine are dichroic in polarized light and will fade when heated sufficiently or exposed to UV light. They may occur together in the same crystal as “smoky citrine.” Smoky quartz can also be converted to citrine by careful heat treatment. Alternatively, it has been suggested that the color of citrine may be due to trace amounts of iron, but synthetic crystals grown in iron-rich solutions have failed to replicate the color or dichroism of natural citrine. The UV-sensitivity of natural citrine further indicates that its color is not caused solely by trace elements.[39]

Natural citrine is rare; most commercial citrine is heat-treated amethyst or smoky quartz. Amethyst loses its natural violet color when heated to above 200-300°C and turns a color that resembles natural citrine, but is often more brownish.[46] Unlike natural citrine, the color of heat-treated amethyst comes from trace amounts of the iron oxide minerals hematite and goethite. Clear quartz with iron inclusions or limonite staining may also resemble natural citrine.[39] Like amethyst, heat-treated amethyst often exhibits color zoning, or uneven color distribution throughout the crystal. In geodes and clusters, the color is usually deepest near the tips.[46] This does not occur in natural citrine.

It is nearly impossible to differentiate between cut citrine and yellow topaz visually, but they differ in hardness. Brazil is the leading producer of citrine, with much of its production coming from the state of Rio Grande do Sul. The name is derived from the Latin word citrina which means "yellow" and is also the origin of the word "citron".[47] Citrine has been referred to as the "merchant's stone" or "money stone", due to a superstition that it would bring prosperity.[48]

Citrine was first appreciated as a golden-yellow gemstone in Greece between 300 and 150 BC, during the Hellenistic Age. Yellow quartz was used prior to that to decorate jewelry and tools but it was not highly sought after.[49]

Milky quartz

[edit]Milk quartz or milky quartz is the most common variety of crystalline quartz. The white color is caused by minute fluid inclusions of gas, liquid, or both, trapped during crystal formation,[50] making it of little value for optical and quality gemstone applications.[51]

Rose quartz

[edit]Rose quartz is a type of quartz that exhibits a pale pink to rose red hue. The color is usually considered as due to trace amounts of titanium, iron, or manganese in the material. Some rose quartz contains microscopic rutile needles that produce asterism in transmitted light. Recent X-ray diffraction studies suggest that the color is due to thin microscopic fibers of possibly dumortierite within the quartz.[52]

Additionally, there is a rare type of pink quartz (also frequently called crystalline rose quartz) with color that is thought to be caused by trace amounts of phosphate or aluminium. The color in crystals is apparently photosensitive and subject to fading. The first crystals were found in a pegmatite found near Rumford, Maine, US, and in Minas Gerais, Brazil.[53] The crystals found are more transparent and euhedral, due to the impurities of phosphate and aluminium that formed crystalline rose quartz, unlike the iron and microscopic dumortierite fibers that formed rose quartz.[54]

Smoky quartz

[edit]Smoky quartz is a gray, translucent version of quartz. It ranges in clarity from almost complete transparency to a brownish-gray crystal that is almost opaque. Some can also be black. The translucency results from natural irradiation acting on minute traces of aluminum in the crystal structure.[55]

Prase

[edit]Prase is a leek-green variety of quartz that gets its color from inclusions of the amphibole actinolite.[56][57] However, the term has also variously been used for a type of quartzite, a microcrystalline variety of quartz or jasper, or any leek-green quartz.[57]

Prasiolite

[edit]Prasiolite, also known as vermarine, is a variety of quartz that is green in color.[58] The green is caused by iron ions.[56] It is a rare mineral in nature and is typically found with amethyst; most "prasiolite" is not natural – it has been artificially produced by heating of amethyst. Since 1950[citation needed], almost all natural prasiolite has come from a small Brazilian mine, but it is also seen in Lower Silesia in Poland. Naturally occurring prasiolite is also found in the Thunder Bay area of Canada.[58]

Piezoelectricity

[edit]Quartz crystals have piezoelectric properties; they develop an electric potential upon the application of mechanical stress.[59] Quartz's piezoelectric properties were discovered by Jacques and Pierre Curie in 1880.[60][61]

Occurrence

[edit]

Quartz is a defining constituent of granite and other felsic igneous rocks. It is very common in sedimentary rocks such as sandstone and shale. It is a common constituent of schist, gneiss, quartzite and other metamorphic rocks.[22] Quartz has the lowest potential for weathering in the Goldich dissolution series and consequently it is very common as a residual mineral in stream sediments and residual soils. Generally a high presence of quartz suggests a "mature" rock, since it indicates the rock has been heavily reworked and quartz was the primary mineral that endured heavy weathering.[62]

While the majority of quartz crystallizes from molten magma, quartz also chemically precipitates from hot hydrothermal veins as gangue, sometimes with ore minerals like gold, silver and copper. Large crystals of quartz are found in magmatic pegmatites.[22] Well-formed crystals may reach several meters in length and weigh hundreds of kilograms.[63]

The largest documented single crystal of quartz was found near Itapore, Goiaz, Brazil; it measured approximately 6.1 m × 1.5 m × 1.5 m (20 ft × 5 ft × 5 ft) and weighed over 39,900 kg (88,000 lb).[64]

Mining

[edit]Quartz is extracted from open pit mines. Miners occasionally use explosives to expose deep pockets of quartz. More frequently, bulldozers and backhoes are used to remove soil and clay and expose quartz veins, which are then worked using hand tools. Care must be taken to avoid sudden temperature changes that may damage the crystals.[65][66]

Related silica minerals

[edit]

Tridymite and cristobalite are high-temperature polymorphs of SiO2 that occur in high-silica volcanic rocks. Coesite is a denser polymorph of SiO2 found in some meteorite impact sites and in metamorphic rocks formed at pressures greater than those typical of the Earth's crust. Stishovite is a yet denser and higher-pressure polymorph of SiO2 found in some meteorite impact sites.[68] Moganite is a monoclinic polymorph. Lechatelierite is an amorphous silica glass SiO2 which is formed by lightning strikes in quartz sand.[69]

Safety

[edit]As quartz is a form of silica, it is a possible cause for concern in various workplaces. Cutting, grinding, chipping, sanding, drilling, and polishing natural and manufactured stone products can release hazardous levels of very small, crystalline silica dust particles into the air that workers breathe.[70] Crystalline silica of respirable size is a recognized human carcinogen and may lead to other diseases of the lungs such as silicosis and pulmonary fibrosis.[71][72]

Synthetic and artificial treatments

[edit]

Not all varieties of quartz are naturally occurring. Some clear quartz crystals can be treated using heat or gamma-irradiation to induce color where it would not otherwise have occurred naturally. Susceptibility to such treatments depends on the location from which the quartz was mined.[73]

Prasiolite, an olive colored material, is produced by heat treatment;[74] natural prasiolite has also been observed in Lower Silesia in Poland.[75] Although citrine occurs naturally, the majority is the result of heat-treating amethyst or smoky quartz.[74] Carnelian has been heat-treated to deepen its color since prehistoric times.[76]

Because natural quartz is often twinned, synthetic quartz is produced for use in industry. Large, flawless, single crystals are synthesized in an autoclave via the hydrothermal process.[77][22][78]

Like other crystals, quartz may be coated with metal vapors to give it an attractive sheen.[79][80]

Uses

[edit]Quartz is the most common material identified as the mystical substance maban in Australian Aboriginal mythology. It is found regularly in passage tomb cemeteries in Europe in a burial context, such as Newgrange or Carrowmore in Ireland. Quartz was also used in Prehistoric Ireland, as well as many other countries, for stone tools; both vein quartz and rock crystal were knapped as part of the lithic technology of the prehistoric peoples.[81]

While jade has been since earliest times the most prized semi-precious stone for carving in East Asia and Pre-Columbian America, in Europe and the Middle East the different varieties of quartz were the most commonly used for the various types of jewelry and hardstone carving, including engraved gems and cameo gems, rock crystal vases, and extravagant vessels. The tradition continued to produce objects that were very highly valued until the mid-19th century, when it largely fell from fashion except in jewelry. Cameo technique exploits the bands of color in onyx and other varieties.

Efforts to synthesize quartz began in the mid-nineteenth century as scientists attempted to create minerals under laboratory conditions that mimicked the conditions in which the minerals formed in nature: German geologist Karl Emil von Schafhäutl (1803–1890) was the first person to synthesize quartz when in 1845 he created microscopic quartz crystals in a pressure cooker.[82] However, the quality and size of the crystals that were produced by these early efforts were poor.[83]

Elemental impurity incorporation strongly influences the ability to process and utilize quartz. Naturally occurring quartz crystals of extremely high purity, necessary for the crucibles and other equipment used for growing silicon wafers in the semiconductor industry, are expensive and rare. These high-purity quartz are defined as containing less than 50 ppm of impurity elements.[84] A major mining location for high purity quartz is the Spruce Pine Gem Mine in Spruce Pine, North Carolina, United States.[85] Quartz may also be found in Caldoveiro Peak, in Asturias, Spain.[86]

By the 1930s, the electronics industry had become dependent on quartz crystals. The only source of suitable crystals was Brazil; however, World War II disrupted the supplies from Brazil, so nations attempted to synthesize quartz on a commercial scale. German mineralogist Richard Nacken (1884–1971) achieved some success during the 1930s and 1940s.[87] After the war, many laboratories attempted to grow large quartz crystals. In the United States, the U.S. Army Signal Corps contracted with Bell Laboratories and with the Brush Development Company of Cleveland, Ohio to synthesize crystals following Nacken's lead.[88][89] (Prior to World War II, Brush Development produced piezoelectric crystals for record players.) By 1948, Brush Development had grown crystals that were 1.5 inches (3.8 cm) in diameter, the largest at that time.[90][91] By the 1950s, hydrothermal synthesis techniques were producing synthetic quartz crystals on an industrial scale, and today virtually all the quartz crystal used in the modern electronics industry is synthetic.[78]

An early use of the piezoelectricity of quartz crystals was in phonograph pickups. One of the most common piezoelectric uses of quartz today is as a crystal oscillator. The quartz oscillator or resonator was first developed by Walter Guyton Cady in 1921.[92][93] George Washington Pierce designed and patented quartz crystal oscillators in 1923.[94][95][96] The quartz clock is a familiar device using the mineral. Warren Marrison created the first quartz oscillator clock based on the work of Cady and Pierce in 1927.[97] The resonant frequency of a quartz crystal oscillator is changed by mechanically loading it, and this principle is used for very accurate measurements of very small mass changes in the quartz crystal microbalance and in thin-film thickness monitors.[98]

-

Rock crystal jug with cut festoon decoration by Milan workshop from the second half of the 16th century, National Museum in Warsaw. The city of Milan, apart from Prague and Florence, was the main Renaissance centre for crystal cutting.[99]

-

Synthetic quartz crystals produced in the autoclave shown in Western Electric's pilot hydrothermal quartz plant in 1959

-

Fatimid ewer in carved rock crystal (clear quartz) with gold lid, c. 1000

Almost all the industrial demand for quartz crystal (used primarily in electronics) is met with synthetic quartz produced by the hydrothermal process. However, synthetic crystals are less prized for use as gemstones.[100] The popularity of crystal healing has increased the demand for natural quartz crystals, which are now often mined in developing countries using primitive mining methods, sometimes involving child labor.[101]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "Quartz". A Dictionary of Geology and Earth Sciences. Oxford University Press. 19 September 2013. ISBN 978-0-19-965306-5.

- ^ Warr, L.N. (2021). "IMA–CNMNC approved mineral symbols". Mineralogical Magazine. 85 (3): 291–320. Bibcode:2021MinM...85..291W. doi:10.1180/mgm.2021.43. S2CID 235729616.

- ^ a b c Deer, W. A.; Howie, R.A.; Zussman, J. (1966). An introduction to the rock-forming minerals. New York: Wiley. pp. 340–355. ISBN 0-582-44210-9.

- ^ Antao, S. M.; Hassan, I.; Wang, J.; Lee, P. L.; Toby, B. H. (1 December 2008). "State-Of-The-Art High-Resolution Powder X-Ray Diffraction (HRPXRD) Illustrated with Rietveld Structure Refinement of Quartz, Sodalite, Tremolite, and Meionite". The Canadian Mineralogist. 46 (6): 1501–1509. doi:10.3749/canmin.46.5.1501.

- ^ Kihara, K. (1990). "An X-ray study of the temperature dependence of the quartz structure". European Journal of Mineralogy. 2 (1): 63–77. Bibcode:1990EJMin...2...63K. doi:10.1127/ejm/2/1/0063. hdl:2027.42/146327.

- ^ Quartz Archived 14 December 2005 at the Wayback Machine. Mindat.org. Retrieved 2013-03-07.

- ^ Anthony, John W.; Bideaux, Richard A.; Bladh, Kenneth W.; Nichols, Monte C., eds. (29 January 1990). "Quartz" (PDF). Handbook of Mineralogy. Vol. III (Halides, Hydroxides, Oxides). Chantilly, VA: Mineralogical Society of America. ISBN 0962209724. Archived (PDF) from the original on 1 April 2010. Retrieved 21 October 2009.

- ^ Quartz Archived 12 November 2006 at the Wayback Machine. Webmineral.com. Retrieved 2013-03-07.

- ^ Hurlbut, Cornelius S.; Klein, Cornelis (1985). Manual of Mineralogy (20 ed.). Wiley. ISBN 0-471-80580-7.

- ^ Anderson, Robert S.; Anderson, Suzanne P. (2010). Geomorphology: The Mechanics and Chemistry of Landscapes. Cambridge University Press. p. 187. ISBN 978-1-139-78870-0.

- ^ "Quartz". Merriam-Webster.com Dictionary. Retrieved 9 January 2024.

- ^ Digitales Wörterbuch der deutschen Sprache Archived 1 December 2017 at the Wayback Machine (in German)

- ^ "Quartz | Definition of quartz by Lexico". Archived from the original on 1 December 2017. Retrieved 26 November 2017.

- ^ Mineral Atlas[usurped], Queensland University of Technology. Mineralatlas.com. Retrieved 2013-03-07.

- ^ Tomkeieff, S.I. (1942). "On the origin of the name 'quartz'". Mineralogical Magazine. 26 (176): 172–178. Bibcode:1942MinM...26..172T. doi:10.1180/minmag.1942.026.176.04.

- ^ Tomkeieff, S.I. (1942). "On the origin of the name 'quartz'" (PDF). Mineralogical Magazine. 26 (176): 172–178. Bibcode:1942MinM...26..172T. doi:10.1180/minmag.1942.026.176.04. Archived (PDF) from the original on 4 September 2015. Retrieved 12 August 2015.

- ^ Morgado, Antonio; Lozano, José Antonio; García Sanjuán, Leonardo; Triviño, Miriam Luciañez; Odriozola, Carlos P.; Irisarri, Daniel Lamarca; Flores, Álvaro Fernández (December 2016). "The allure of rock crystal in Copper Age southern Iberia: Technical skill and distinguished objects from Valencina de la Concepción (Seville, Spain)". Quaternary International. 424: 232–249. Bibcode:2016QuInt.424..232M. doi:10.1016/j.quaint.2015.08.004.

- ^ Nesse, William D. (2000). Introduction to mineralogy. New York: Oxford University Press. p. 205. ISBN 9780195106916.

- ^ Pliny the Elder, The Natural History, Book 37, Chapter 9. Available on-line at: Perseus.Tufts.edu Archived 9 November 2012 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Tutton, A.E. (1910). "Rock crystal: its structure and uses". RSA Journal. 59: 1091. JSTOR 41339844.

- ^ Nicolaus Steno (Latinized name of Niels Steensen) with John Garrett Winter, trans., The Prodromus of Nicolaus Steno's Dissertation Concerning a Solid Body Enclosed by Process of Nature Within a Solid (New York, New York: Macmillan Co., 1916). On page 272 Archived 4 September 2015 at the Wayback Machine, Steno states his law of constancy of interfacial angles: "Figures 5 and 6 belong to the class of those which I could present in countless numbers to prove that in the plane of the axis both the number and the length of the sides are changed in various ways without changing the angles; … "

- ^ a b c d e Hurlbut & Klein 1985.

- ^ Nesse 2000, p. 202–204.

- ^ Sinkankas, John (1964). Mineralogy for amateurs. Princeton, N.J.: Van Nostrand. pp. 443–447. ISBN 0442276249.

- ^ Tarr, W. A (1929). "Doubly terminated quartz crystals occurring in gypsum". American Mineralogist. 14 (1): 19–25. Retrieved 7 April 2021.

- ^ Crystal Data, Determinative Tables, ACA Monograph No. 5, American Crystallographic Association, 1963

- ^ Nesse 2000, p. 201.

- ^ Johnson, Scott E.; Song, Won Joon; Cook, Alden C.; Vel, Senthil S.; Gerbi, Christopher C. (1 January 2021). "The quartz α↔β phase transition: Does it drive damage and reaction in continental crust?". Earth and Planetary Science Letters. 553: 116622. Bibcode:2021E&PSL.55316622J. doi:10.1016/j.epsl.2020.116622. ISSN 0012-821X.

- ^ Knapek, Michal; Húlan, Tomáš; Minárik, Peter; Dobroň, Patrik; Štubňa, Igor; Stráská, Jitka; Chmelík, František (January 2016). "Study of microcracking in illite-based ceramics during firing". Journal of the European Ceramic Society. 36 (1): 221–226. doi:10.1016/j.jeurceramsoc.2015.09.004.

- ^ Tomás, R.; Cano, M.; Pulgarín, L. F.; Brotóns, V.; Benavente, D.; Miranda, T.; Vasconcelos, G. (1 November 2021). "Thermal effect of high temperatures on the physical and mechanical properties of a granite used in UNESCO World Heritage sites in north Portugal". Journal of Building Engineering. 43: 102823. doi:10.1016/j.jobe.2021.102823. hdl:10045/115630. ISSN 2352-7102.

- ^ Johnson, Scott E.; Song, Won Joon; Cook, Alden C.; Vel, Senthil S.; Gerbi, Christopher C. (January 2021). "The quartz α↔β phase transition: Does it drive damage and reaction in continental crust?". Earth and Planetary Science Letters. 553: 116622. Bibcode:2021E&PSL.55316622J. doi:10.1016/j.epsl.2020.116622. S2CID 225116168.

- ^ "Quartz Gemstone and Jewelry Information: Natural Quartz – GemSelect". www.gemselect.com. Archived from the original on 29 August 2017. Retrieved 29 August 2017.

- ^ Heaney, Peter J. (1994). "Structure and Chemistry of the low-pressure silica polymorphs". Reviews in Mineralogy and Geochemistry. 29 (1): 1–40. Archived from the original on 24 July 2011. Retrieved 26 October 2009.

- ^ "Agate". www.mindat.org. Retrieved 21 January 2025.

- ^ "Onyx". www.mindat.org. Retrieved 21 January 2025.

- ^ "Jasper". www.mindat.org. Retrieved 21 January 2025.

- ^ "Quartz: The gemstone Quartz information and pictures". www.minerals.net. Archived from the original on 27 August 2017. Retrieved 29 August 2017.

- ^ Lehmann, G.; Moore, W. J. (20 May 1966). "Color Center in Amethyst Quartz". Science. 152 (3725): 1061–1062. Bibcode:1966Sci...152.1061L. doi:10.1126/science.152.3725.1061. PMID 17754816. S2CID 29602180.

- ^ a b c "Citrine". www.mindat.org. Retrieved 10 January 2025.

- ^ "Ametrine". www.mindat.org. Retrieved 10 January 2025.

- ^ a b "Quartz (var. ametrine) | Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History". naturalhistory.si.edu. Retrieved 10 January 2025.

- ^ "Blue Quartz". Mindat.org. Archived from the original on 24 February 2017. Retrieved 24 February 2017.

- ^ a b Oldershaw, Cally (2003). Firefly Guide to Gems. Firefly Books. pp. 100. ISBN 9781552978146. Retrieved 19 February 2017.

- ^ "The Gemstone Dumortierite". Minerals.net. Archived from the original on 6 May 2017. Retrieved 23 April 2017.

- ^ Friedman, Herschel. "THE GEMSTONE DUMORTIERITE". Minerals.net. Retrieved 28 November 2020.

- ^ a b "Amethyst". www.mindat.org. Retrieved 10 January 2025.

- ^ Citrine Archived 2 May 2010 at the Wayback Machine. Mindat.org (2013-03-01). Retrieved 2013-03-07.

- ^ Webster, Richard (8 September 2012). "Citrine". The Encyclopedia of Superstitions. p. 59. ISBN 9780738725611.

- ^ "Citrine Meaning". 7 January 2016. Archived from the original on 18 August 2017. Retrieved 18 August 2017.

- ^ Hurrell, Karen; Johnson, Mary L. (2016). Gemstones: A Complete Color Reference for Precious and Semiprecious Stones of the World. Book Sales. p. 97. ISBN 978-0-7858-3498-4.

- ^ Milky quartz at Mineral Galleries Archived 19 December 2008 at the Wayback Machine. Galleries.com. Retrieved 2013-03-07.

- ^ "Rose Quartz". Mindat.org. Archived from the original on 1 April 2009. Retrieved 11 May 2023.

- ^ "Quartz and its colored varieties". California Institute of Technology. Archived from the original on 19 July 2011.

- ^ "Pink Quartz". The Quartz Page. Retrieved 11 May 2023.

- ^ Fridrichová, Jana; Bačík, Peter; Illášová, Ľudmila; Kozáková, Petra; Škoda, Radek; Pulišová, Zuzana; Fiala, Anton (July 2016). "Raman and optical spectroscopic investigation of gem-quality smoky quartz crystals". Vibrational Spectroscopy. 85: 71–78. doi:10.1016/j.vibspec.2016.03.028.

- ^ a b Klemme, S.; Berndt, J.; Mavrogonatos, C.; Flemetakis, S.; Baziotis, I.; Voudouris, P.; Xydous, S. (2018). "On the Color and Genesis of Prase (Green Quartz) and Amethyst from the Island of Serifos, Cyclades, Greece". Minerals. 8 (11): 487. Bibcode:2018Mine....8..487K. doi:10.3390/min8110487.

- ^ a b "Prase". www.mindat.org. Retrieved 21 January 2025.

- ^ a b "Prasiolite". quarzpage.de. 28 October 2009. Archived from the original on 13 July 2011. Retrieved 28 November 2010.

- ^ Saigusa, Y. (2017). "Chapter 5 – Quartz-Based Piezoelectric Materials". In Uchino, Kenji (ed.). Advanced Piezoelectric Materials. Woodhead Publishing in Materials (2nd ed.). Woodhead Publishing. pp. 197–233. doi:10.1016/B978-0-08-102135-4.00005-9. ISBN 9780081021354.

- ^ Curie, Jacques; Curie, Pierre (1880). "Développement par compression de l'électricité polaire dans les cristaux hémièdres à faces inclinées" [Development, via compression, of electric polarization in hemihedral crystals with inclined faces]. Bulletin de la Société minéralogique de France. 3 (4): 90–93. doi:10.3406/bulmi.1880.1564.. Reprinted in: Curie, Jacques; Curie, Pierre (1880). "Développement, par pression, de l'électricité polaire dans les cristaux hémièdres à faces inclinées". Comptes rendus. 91: 294–295. Archived from the original on 5 December 2012. Retrieved 17 December 2013.

- ^ Curie, Jacques; Curie, Pierre (1880). "Sur l'électricité polaire dans les cristaux hémièdres à faces inclinées" [On electric polarization in hemihedral crystals with inclined faces]. Comptes rendus. 91: 383–386. Archived from the original on 5 December 2012. Retrieved 17 December 2013.

- ^ Boggs, Sam (2006). Principles of sedimentology and stratigraphy (4th ed.). Upper Saddle River, N.J.: Pearson Prentice Hall. p. 130. ISBN 0131547283.

- ^ Jahns, Richard H. (1953). "The genesis of pegmatites: I. Occurrence and origin of giant crystals". American Mineralogist. 38 (7–8): 563–598. Retrieved 7 April 2021.

- ^ Rickwood, P. C. (1981). "The largest crystals" (PDF). American Mineralogist. 66: 885–907 (903). Archived (PDF) from the original on 25 August 2013. Retrieved 7 March 2013.

- ^ McMillen, Allen. "Quartz Mining". Encyclopedia of Arkansas. Central Arkansas Library System. Retrieved 28 November 2020.

- ^ Eleanor McKenzie (25 April 2017). "How Is Quartz Extracted?". sciencing.com. Retrieved 28 January 2020.

- ^ "Mineral Science" by Cornelis Klein; ISBN 0-471-25177-1

- ^ Nesse 2000, pp. 201–202.

- ^ "Lechatelierite". Mindat.org. Retrieved 7 April 2021.

- ^ Hazard Alert - Worker Exposure to Silica during Countertop Manufacturing, Finishing and Installation (PDF). DHHS (NIOSH). p. 2. Retrieved 27 November 2019.

- ^ "Silica (crystalline, respirable)". OEHHA. California Office of Environmental Health Hazard Assessment. Retrieved 27 November 2019.

- ^ Arsenic, Metals, Fibres and Dusts. A Review of Human Carcinogens (PDF) (100C ed.). International Agency for Research on Cancer. 2012. pp. 355–397. ISBN 978-92-832-1320-8. Retrieved 27 November 2019.

- ^ Liccini, Mark, Treating Quartz to Create Color Archived 23 December 2014 at the Wayback Machine, International Gem Society website. Retrieved 22 December 2014

- ^ a b Henn, U.; Schultz-Güttler, R. (2012). "Review of some current coloured quartz varieties" (PDF). J. Gemmol. 33: 29–43. doi:10.15506/JoG.2012.33.1.29. Retrieved 7 April 2021.

- ^ Platonov, Alexej N.; Szuszkiewicz, Adam (1 June 2015). "Green to blue-green quartz from Rakowice Wielkie (Sudetes, south-western Poland) – a re-examination of prasiolite-related color varieties of quartz". Mineralogia. 46 (1–2): 19–28. Bibcode:2015Miner..46...19P. doi:10.1515/mipo-2016-0004.

- ^ Groman-Yaroslavski, Iris; Bar-Yosef Mayer, Daniella E. (June 2015). "Lapidary technology revealed by functional analysis of carnelian beads from the early Neolithic site of Nahal Hemar Cave, southern Levant". Journal of Archaeological Science. 58: 77–88. Bibcode:2015JArSc..58...77G. doi:10.1016/j.jas.2015.03.030.

- ^ Walker, A. C. (August 1953). "Hydrothermal Synthesis of Quartz Crystals". Journal of the American Ceramic Society. 36 (8): 250–256. doi:10.1111/j.1151-2916.1953.tb12877.x.

- ^ a b Buisson, X.; Arnaud, R. (February 1994). "Hydrothermal growth of quartz crystals in industry. Present status and evolution" (PDF). Le Journal de Physique IV. 04 (C2): C2–25–C2-32. doi:10.1051/jp4:1994204. S2CID 9636198.

- ^ Robert Webster, Michael O'Donoghue (January 2006). Gems: Their Sources, Descriptions and Identification. Butterworth-Heinemann. ISBN 9780750658560.

- ^ "How is Aura Rainbow Quartz Made?". Geology In. 2017. Retrieved 7 April 2021.

- ^ "Driscoll, Killian. 2010. Understanding quartz technology in early prehistoric Ireland". Archived from the original on 25 June 2017. Retrieved 19 July 2017.

- ^ von Schafhäutl, Karl Emil (10 April 1845). "Die neuesten geologischen Hypothesen und ihr Verhältniß zur Naturwissenschaft überhaupt (Fortsetzung)" [The latest geological hypotheses and their relation to science in general (continuation)]. Gelehrte Anzeigen. 20 (72). München: im Verlage der königlichen Akademie der Wissenschaften, in Commission der Franz'schen Buchhandlung: 577–584. OCLC 1478717. From page 578: 5) Bildeten sich aus Wasser, in welchen ich im Papinianischen Topfe frisch gefällte Kieselsäure aufgelöst hatte, beym Verdampfen schon nach 8 Tagen Krystalle, die zwar mikroscopisch, aber sehr wohl erkenntlich aus sechseitigen Prismen mit derselben gewöhnlichen Pyramide bestanden. ( 5) There formed from water in which I had dissolved freshly precipitated silicic acid in a Papin pot [i.e., pressure cooker], after just 8 days of evaporating, crystals, which albeit were microscopic but consisted of very easily recognizable six-sided prisms with their usual pyramids.)

- ^ Byrappa, K. and Yoshimura, Masahiro (2001) Handbook of Hydrothermal Technology. Norwich, New York: Noyes Publications. ISBN 008094681X. Chapter 2: History of Hydrothermal Technology.

- ^ Götze, Jens; Pan, Yuanming; Müller, Axel (October 2021). "Mineralogy and mineral chemistry of quartz: A review". Mineralogical Magazine. 85 (5): 639–664. Bibcode:2021MinM...85..639G. doi:10.1180/mgm.2021.72. ISSN 0026-461X. S2CID 243849577.

- ^ Nelson, Sue (2 August 2009). "Silicon Valley's secret recipe". BBC News. Archived from the original on 5 August 2009. Retrieved 16 September 2009.

- ^ "Caldoveiro Mine, Tameza, Asturias, Spain". mindat.org. Archived from the original on 12 February 2018. Retrieved 15 February 2018.

- ^ Nacken, R. (1950) "Hydrothermal Synthese als Grundlage für Züchtung von Quarz-Kristallen" (Hydrothermal synthesis as a basis for the production of quartz crystals), Chemiker Zeitung, 74 : 745–749.

- ^ Hale, D. R. (1948). "The Laboratory Growing of Quartz". Science. 107 (2781): 393–394. Bibcode:1948Sci...107..393H. doi:10.1126/science.107.2781.393. PMID 17783928.

- ^ Lombardi, M. (2011). "The evolution of time measurement, Part 2: Quartz clocks [Recalibration]" (PDF). IEEE Instrumentation & Measurement Magazine. 14 (5): 41–48. doi:10.1109/MIM.2011.6041381. S2CID 32582517. Archived (PDF) from the original on 27 May 2013. Retrieved 30 March 2013.

- ^ "Record crystal", Popular Science, 154 (2) : 148 (February 1949).

- ^ Brush Development's team of scientists included: Danforth R. Hale, Andrew R. Sobek, and Charles Baldwin Sawyer (1895–1964). The company's U.S. patents included:

- Sobek, Andrew R. "Apparatus for growing single crystals of quartz", U.S. patent 2,674,520; filed: 11 April 1950; issued: 6 April 1954.

- Sobek, Andrew R. and Hale, Danforth R. "Method and apparatus for growing single crystals of quartz", U.S. patent 2,675,303; filed: 11 April 1950; issued: 13 April 1954.

- Sawyer, Charles B. "Production of artificial crystals", U.S. patent 3,013,867; filed: 27 March 1959; issued: 19 December 1961. (This patent was assigned to Sawyer Research Products of Eastlake, Ohio.)

- ^ Cady, W. G. (1921). "The piezoelectric resonator". Physical Review. 17: 531–533. doi:10.1103/PhysRev.17.508.

- ^ "The Quartz Watch – Walter Guyton Cady". The Lemelson Center, National Museum of American History, Smithsonian Institution. Archived from the original on 4 January 2009.

- ^ Pierce, G. W. (1923). "Piezoelectric crystal resonators and crystal oscillators applied to the precision calibration of wavemeters". Proceedings of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences. 59 (4): 81–106. doi:10.2307/20026061. hdl:2027/inu.30000089308260. JSTOR 20026061.

- ^ Pierce, George W. "Electrical system", U.S. patent 2,133,642, filed: 25 February 1924; issued: 18 October 1938.

- ^ "The Quartz Watch – George Washington Pierce". The Lemelson Center, National Museum of American History, Smithsonian Institution. Archived from the original on 4 January 2009.

- ^ "The Quartz Watch – Warren Marrison". The Lemelson Center, National Museum of American History, Smithsonian Institution. Archived from the original on 25 January 2009.

- ^ Sauerbrey, Günter Hans (April 1959) [1959-02-21]. "Verwendung von Schwingquarzen zur Wägung dünner Schichten und zur Mikrowägung" (PDF). Zeitschrift für Physik (in German). 155 (2). Springer-Verlag: 206–222. Bibcode:1959ZPhy..155..206S. doi:10.1007/BF01337937. ISSN 0044-3328. S2CID 122855173. Archived (PDF) from the original on 26 February 2019. Retrieved 26 February 2019. (NB. This was partially presented at Physikertagung in Heidelberg in October 1957.)

- ^ The International Antiques Yearbook. Studio Vista Limited. 1972. p. 78.

Apart from Prague and Florence, the main Renaissance centre for crystal cutting was Milan.

- ^ "Hydrothermal Quartz". Gem Select. GemSelect.com. Retrieved 28 November 2020.

- ^ McClure, Tess (17 September 2019). "Dark crystals: the brutal reality behind a booming wellness craze". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 25 September 2019.

External links

[edit]- Quartz varieties, properties, crystal morphology. Photos and illustrations

- Gilbert Hart, "Nomenclature of Silica", American Mineralogist, Volume 12, pp. 383–395. 1927

- "The Quartz Watch – Inventors". The Lemelson Center, National Museum of American History, Smithsonian Institution. Archived from the original on 7 January 2009.

- Terminology used to describe the characteristics of quartz crystals when used as oscillators

- Quartz use as prehistoric stone tool raw material

![Rock crystal jug with cut festoon decoration by Milan workshop from the second half of the 16th century, National Museum in Warsaw. The city of Milan, apart from Prague and Florence, was the main Renaissance centre for crystal cutting.[99]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/b/b9/Milan_Jug_with_cut_festoon_decoration.jpg/146px-Milan_Jug_with_cut_festoon_decoration.jpg)