Arnaud-Michel d'Abbadie

This article needs additional citations for verification. (September 2023) |

Arnaud-Michel d'Abbadie | |

|---|---|

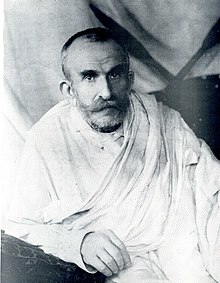

Arnaud-Michel d'Abbadie in Ethiopian clothes a few months before his death in 1893 | |

| Born | 24 July 1815 Dublin, Ireland |

| Died | 8 November 1893 (aged 78) Ciboure, France |

| Nationality | French, Basque |

| Citizenship | France |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Explorer, Geographer |

Arnaud-Michel d'Abbadie d'Arrast (24 July 1815 – 8 November 1893), also listed as Michel Arnaud d'Abbadie in the Chambers Biographical Dictionary[1] was a French-Basque explorer of Irish origin, renowned for his extensive travels in Ethiopia alongside his elder brother, Antoine d'Abbadie d'Arrast. Arnaud distinguished himself as a geographer, ethnologist, and linguist, gaining intimate knowledge of Abyssinian polemarchs and serving as an active observer of their battles and courtly life. In 1868, Arnaud published the seminal account of their travels, titled Douze ans de séjour dans la Haute-Ethiopie, providing a comprehensive narrative of their twelve-year sojourn in the region.

Early life

[edit]Arnaud's father, Michel Arnauld d'Abbadie (1772–1832), hailed from an ancient family of lay abbots in Arrast, a commune in the canton of Mauléon. In 1791, to escape the repercussions of the French Revolution, Michel Arnauld emigrated, first to Spain and later to England and Ireland, where he became a shipowner, specializing in the importation of Spanish wines. On 18 July 1807, he married Eliza Thompson of Park (1779–1865), the daughter of a doctor, in Thurles, County Tipperary.[2]

Arnaud d'Abbadie, born in Dublin on 24 July 1815, was the fourth child and second son in a family of six siblings:[3]

- Elisa (1808–1875);

- Antoine (1810–1896);

- Celina (1811–1894),

- Arnaud Michel (1815–1893);

- Julia (1820–1900);

- Charles Jean (1821–1901).

In 1820, Michel Arnauld returned to France and obtained royal permission from Louis XVIII to append d’Arrast to the family name, becoming d’Abbadie d’Arrast.

1815–1836

[edit]Like his elder brother Antoine, Arnaud was educated at home by a governess until the age of 12, when he enrolled at the Lycée Henri IV in Paris. Gifted with a remarkable aptitude for languages, Arnaud became fluent in English, Latin, and Greek during his formative years.

At the age of seventeen, Arnaud d’Abbadie was intrigued by Freemasonry after hearing his friends describe it as a benevolent society devoted to philanthropy. Curiosity led him to seek affiliation. However, during the initiation ceremony, he was asked to swear an oath of secrecy to safeguard the sect’s secrets. This pivotal moment brought a sudden revelation: “If these men hide, it must be because they are guilty. Only those ashamed of their actions flee the light,” he thought. Declining to make what he deemed an imprudent promise, he turned away from the organization.[4]

When the time came to decide on a path for his future, Arnaud instinctively gravitated toward a military career. He was a soldier by nature. During that era, the conquest of Algeria seized public attention, and the young man was inflamed with the desire to participate in the campaign. However, his mother’s resolve restrained him. A fervent patriot, though French by marriage, she was the last direct descendant of the Thomson of Park family and could not bear the thought of her son pursuing a path that might one day require him to take up arms against England. To steer him away from such aspirations, she sent Arnaud to his ancestral homeland in the Basque Country, where exile had only briefly interrupted the enduring legacy of his lineage. There, he became deeply enamored with his heritage: he mastered its language, immersed himself in its traditions, and explored its lands extensively. He lived with his brother Antoine at the castle of Audaux.[5]

Civil war had just erupted in Spain. At the head of the Carlist troops, Zumalacárregui was making Europe resound with the echoes of his exploits. Each night, crowds of French Basques crossed the border to join their Spanish brethren. Arnaud, too, was about to enlist when a friend, an officer in the French army, opened a new horizon to him: “Come with me to Algeria,” he said. “The stirring emotions of action appeal to your adventurous spirit, and you will find your share of them. Even if you do not fall for France, you will nonetheless serve your country, for you will have the opportunity to gather the instructive and valuable insights that a true observer gleans from the field of action.”

The young man endeavored to follow his friend’s plan. Yet this passive role as a mere witness stirred sorrowful thoughts within his soul. He trembled with impatience. The news of the capture of Constantine, at the assault on which he had wished to be present, only deepened his regret. He left Africa and embarked for France.[6]

Since filial respect forbade him from serving his country under arms, Arnaud resolved instead to contribute to the advancement of science. Aware of his elder brother’s intention to explore Abyssinia, he decided to join the expedition, driven by the shared ambition of locating the sources of the Nile.

Exploration of Abyssinia (1837–1849)

[edit]Antoine and Arnaud spent twelve years exploring Abyssinia, a region that remained largely unknown to Europeans in the nineteenth century, even as Africa increasingly became the focus of exploration. At the time, European expeditions were often confined to major rivers, leaving vast areas uncharted. The Horn of Africa, particularly the Harar-Mogadishu-Cape Guardafui, was a blank space on maps as late as 1840. Similarly, the geography, geodesy, geology, and ethnography of much of the continent were still shrouded in mystery.

The challenges were immense. Abyssinia’s provinces spanned over 300,000 square kilometers, presenting a vast and complex terrain. The political landscape was equally precarious: wars were frequent, and allies could swiftly turn into enemies. Historians refer to this turbulent period as the Era of Princes, or Zemene Mesafint. Language barriers further compounded their difficulties; Ethiopia’s alphabet, comprising 267 characters, served nearly thirty distinct languages. Endemic diseases such as typhus, leprosy, and ophthalmia posed constant threats. Adding to these hardships were the suspicions of colonial powers, as the British, Italians, Germans, and Turks all suspected the d’Abbadie brothers of engaging in espionage under the guise of scientific exploration.

Despite these obstacles, the brothers pursued distinct yet complementary objectives. Arnaud, an ethnologist, focused on studying the diverse peoples he encountered, meticulously documenting their cultures, customs, and ways of life. Antoine, meanwhile, concentrated on locating the sources of the Nile, mapping the country, and conducting geodetic and astronomical measurements. His innovative techniques produced maps that were unmatched in accuracy until the advent of aerial and satellite photography.

Both Arnaud and Antoine were devout Catholics, hailing from a family of lay abbots. Antoine once remarked that, but for the events of 1793, he would have signed his name as "Antoine d’Abbadie, abbé lai d’Arrast en Soule." Their religious convictions played a significant role in their mission. They ventured into the Ethiopian mountains with the dual aim of supporting the Christian faith, threatened by the spread of Islam, and seeking to restore the former Christian Empire of Ethiopia. Arnaud, in particular, hoped to align the Ethiopian state in an alliance with France, thereby countering British expansion in East Africa.[7]

To navigate the complexities of Abyssinia, the brothers understood the necessity of thorough preparation. Before departing from France, they gathered extensive knowledge about the country’s customs, traditions, and political climate. Their keen observations on ethnology, linguistics, and politics became invaluable contributions to the understanding of a region that had long eluded European comprehension.

Stay in Abyssinia

[edit]The two brothers displayed markedly different personalities. Antoine, the scientist, was the more conciliatory of the two, achieving his objectives through perseverance and patience. Adopting the persona of an Ethiopian scholar, or memhir, he dressed in traditional attire and walked barefoot, as sandals were reserved for lepers and Jews. His dedication to cultural assimilation earned him the title "the man of the book."

Arnaud, by contrast, was flamboyant and bold, distinguishing himself through his dynamic interactions with princes and warlords. He participated in battles, often risking his life, and forged deep ties with influential figures. Among them was Dejazmach Goshu, prince of Gojjam, who regarded Arnaud as a son. Known as "Ras Michael," Arnaud became both a trusted confidant and a key figure in the political and military affairs of the region.

In 1987 the historian, jurist, linguist and high Ethiopian official Berhanou Abebe published verses, distiches from the Era of Princes which refer to Arnaud ("ras Michael"): "I have not even provisions to offer them, / Let the earth devour me in the place of the men of ras Michael. / Is it an oversight of the embosser or the lack of bronze / That the scabbard of Michael's saber has no ornamentation?.[8]

For tactical reasons, Arnaud and Antoine traveled separately and spent limited time together, although they maintained regular correspondence. They united their efforts for the Ennarea expedition into Oromo territory, aiming to uncover the source of the White Nile.

Typically, Arnaud took the lead in laying the groundwork, making initial visits and establishing connections with local lords. Once these relationships were secured, Antoine worked discreetly, gathering crucial information on Ethiopia’s geography, geology, archaeology, and natural history. This complementary approach allowed them to navigate the complexities of their mission with greater effectiveness. Their extensive exploration concluded with their return to France in early 1849.

1850–1893

[edit]On 26 July 1850 Antoine and Arnaud d'Abbadie d'Arrast received the gold medal of the Société de Géographie.[9] On September 27, 1850, the two brothers were made knights of the Legion of Honor.[10]

Return to Ethiopia

[edit]Arnaud returned to France with a clear objective: the realization of his ambitious project to reconstruct the ancient Christian empire of Ethiopia, with Dejazmach Goshu as its leader. He presented his proposal to the French government through the Duke of Bassano. The response was favorable, and although Arnaud was not granted an official diplomatic mission, he was entrusted with delivering gifts to Dejazmach Goshu on behalf of France to foster an alliance. However, honoring a request from his mother, Arnaud pledged not to cross the Tekezé River—a tributary of the Black Nile located along the western border of Tigray—so that he could maintain an accessible route to the sea for his return to France.

Upon his arrival in Massawa, news of the return of "Ras Michael" circulated, signaling that Dejazmach Goshu eagerly awaited his friend’s arrival. Unfortunately, Goshu was located on the opposite side of the Tekezé, in Gojjam, making it impossible for Arnaud to meet him without breaking his promise. Despite this limitation, Arnaud and Goshu maintained a prolific correspondence, exchanging numerous letters. Arnaud, however, remained resolutely committed to his oath and refrained from crossing the river.

In November 1852, the Battle of Gur Amba marked a pivotal moment, ending with the death of Dejazmach Goshu and the triumph of Kassa Hailou, who would later ascend to power as Emperor Tewodros II.

For Arnaud, this event was a devastating blow. He had not only lost a close friend but also seen his hopes of restoring a Christian empire in Ethiopia extinguished. Overwhelmed by despair, he returned to France at the end of December 1852, disillusioned by the collapse of his visionary project.

Arnaud’s final attempt to strengthen ties between France and Ethiopia took place during the 1860s, a period marked by escalating tensions in the region. The British had established a formidable presence in Sudan, Aden, and Somalia, heightening the likelihood of a confrontation with Emperor Tewodros II of Ethiopia. Recognizing the strategic importance of Ethiopia, Arnaud sought an audience with Napoleon III to advocate for French involvement. He presented a case highlighting the potential benefits France could offer Ethiopia and the advantages of a Franco-Ethiopian alliance. Although Napoleon III received Arnaud courteously and listened attentively, he ultimately declined to take action, citing France’s obligations under existing alliances with England. Arnaud’s hopes of fostering cooperation were thus thwarted. In 1868, a British military expedition was launched against Ethiopia, culminating in the tragic conclusion of Emperor Tewodros II’s reign with his suicide.

Second marriage and children

[edit]Arnaud married Elisabeth West Young, an American and the daughter of Robert West Young (1805–1880), a physician, and Anne Porter Webb.

They had nine children:[11]

- Anne Elisabeth (1865–1918) ;

- Michel Robert (1866–1900) ;

- Thérèse (1867–1945) ;

- Ferdinand Guilhem (1870–1915)

- Marie-Angèle (1871–1955) ;

- Camille Arnauld (1873–1968) ;

- Jéhan Augustin (1874–1912) ;

- Martial (1878–1914) ;

- Marc Antoine (1883–1914).

In Paris, Arnaud hosted a salon at his residence on the rue de Grenelle, which became a regular meeting place for intellectual and educated individuals. Despite the prestige associated with such gatherings, Arnaud held a deep aversion to worldliness and ultimately decided to leave Paris. Seeking a quieter life, he relocated with his family to the Basque Country, where he commissioned the construction of the château of Elhorriaga in Ciboure. The castle was designed by the architect Lucien Cottet. During the Second World War, the castle was requisitioned and occupied by the Wehrmacht. It was demolished in 1985 to make way for a real estate development project.[12]

Life in Ciboure and death

[edit]

In Ciboure he quickly gained a reputation as a charitable man, but always remained discreet. The first volume of the account of travels in Ethiopia was published by Arnauld in 1868 under the title Twelve years in Upper Ethiopia. It recounts the period 1837–1841. The next three volumes were not published during his lifetime. Volume 1 was translated for the first time in 2016 into the Ethiopian language and Volume 2 in 2020 under the title "በኢትዮጵያ ከፍተኛ ተራሮች ቆይታዬ" (My stay in the high mountains of Ethiopia).

Arnaud died on 8 November 1893; he is buried in the cemetery of Ciboure. The photograph in Ethiopian clothes was taken shortly before his death.

The memory of "Ras Michael" remained alive in Ethiopia for a long time, indeed Emperor Menelik II and his wife referred to him:

[…] "He had, in his person, made to love the France. And if we have sympathies among this people today, the old men and Menelik himself will tell you the reason: "We have not forgotten Ras Michael..."[13]"..

Publications on Ethiopia

[edit]| Year | Area of Study | Title | Translation | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1868 | Ethiopia | Douze ans de séjour dans la Haute-Éthiopie volume 1 | Twelve years in Upper Ethiopia volume 1 | On Academia (in English) |

| 1980 | Ethiopia | Douze ans de séjour dans la Haute-Éthiopie volume 2 | Twelve years in Upper Ethiopia volume 2 | On Ebin (in French) |

| 1983 | Ethiopia | Douze ans de séjour dans la Haute-Éthiopie volume 3 | Twelve years in Upper Ethiopia volume 3 | On Ebin (in French) |

| 1999 | Ethiopia | Douze ans de séjour dans la Haute-Éthiopie volume 4 | Twelve years in Upper Ethiopia volume 4 | On Dokumen (in French) |

References

[edit]- ^ Thorne 1984, p. 1

- ^ Goyhenetche, Manex. Antoine d'Abbadie intermédiaire social et culturel du Pays Basque du XIXe siècle? (PDF).

- ^ Malecot, Georges (1971). "Les voyageurs français et les relations entre la France et l'Abyssinie de 1835 à 1870". Revue Française d'Histoire d'Outre-Mer. 58 (211). Outre-Mers. Revue d'histoire: 151. doi:10.3406/outre.1971.1537.

- ^ d'Arnély, G. (1898). Arnauld d'Abbadie, explorateur de l'Ethiopie (1815-1893) (PDF) (in French). Les Contemporains. p. 2.

- ^ Darboux, Gaston (1908). "Notice Historique sur Antoine d'Abbadie". Gallica. Mémoires de l'Académie des sciences de l'Institut de France: 35-103.

- ^ d'Arnély, G. (1898). Arnauld d'Abbadie, explorateur de l'Ethiopie (1815-1893) (PDF) (in French). Les Contemporains. p. 3.

- ^ Bernoville, Gaëtan (May 1950). L'épopée missionnaire d'Éthiopie: Monseigneur Jarosseau et la mission de Gallas. Paris: Albin Michel.

- ^ Abebe, Berhanou (1987). ""Distiques du Zamana asafent", Annales d'Éthiopie". Annales d'Éthiopie. 14 (1): 32-33. doi:10.3406/ethio.1987.930.

- ^ Daussay, P (1850). "Rapport de la Commission du concours au prix annuel pour la découverte la plus importante en géographie". Vol. 14. Bulletin de la Société de Géographie. p. 10-28.

- ^ Dumas, J (October 4, 1850). Rapport au Président de la république: Légion d'honneur. Journal des débats politiques et littéraires.

- ^ Arbre genéologique d'Arnauld d'Abbadie. Geneanet.

- ^ Une vigie de l'histoire. Sud-Ouest.

- ^ d'Arnély, G. (1898). Arnauld d'Abbadie, explorateur de l'Ethiopie (1815-1893) (PDF) (in French). Les Contemporains. p. 1-16.

Bibliography

[edit]- Nicaise, Auguste (1868). Compte rendu : Douze ans dans la Haute Éthiopie (Abyssinie) (in French). Bulletin de la Société géographique. p. 389-398.

- d'Arnély, G. (1898). Arnauld d'Abbadie, explorateur de l'Ethiopie (1815-1893) (PDF) (in French). Les Contemporains. p. 1-16.

- Morié, Louis J. (1904). Histoire de l'Éthiopie (Nubie et Abyssinie) depuis les temps les plus reculés jusqu'à nos jours (in French). Paris: A. Challamel. p. 500.

- Pérès, Jacques-Noël (2012). "Arnauld d'Abbadie d'Arrast et le voyage aux sources du Nil". Transversalités (in French). 122 (2): 29-42. doi:10.3917/trans.122.0029.

- Perret, Michel (1986). "Villes impériales, villes princières : note sur le caractère des villes dans l'Éthiopie du XVIIIe siècle". Journal des Africanistes (in French). 56 (2): 55-65. doi:10.3406/jafr.1986.2143.

- Tubiana, Joseph. "Les moissons du voyageur ou l'aventure scientifique des frères d'Abbadie (1838-1848)". Euskonews & Média (in French).

- Crummey, Donald (2000). Land and Society in the Christian Kingdom of Ethiopia. James Currey Publisher. p. 373. ISBN 9780852557631.

- Blundell, Herbert Weld (1922). The Royal chronicle of Abyssinia, 1769-1840. London: Cambridge: University Press. p. 384-390.

- Ficquet, Éloi (2010). "La mixité religieuse comme stratégie politique. La dynastie des Māmmadoč du Wallo (Éthiopie centrale), du milieu du XVIIIe siècle au début du XXe siècle". Afriques (in French) (1). doi:10.4000/afriques.533.

- Ficquet, Éloi (2017). "Notes manuscrites d'Arnauld d'Abbadie sur l'administration des établissements religieux en Éthiopie dans les années 1840-1850". Archive ouverte en Sciences de l'Homme et de la Société (in French).

- Hoiberg, Dale H., ed. (2010). "Abbadie, Antoine-Thomson d'; and Abbadie, Arnaud-Michel d'". Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. I: A-Ak - Bayes (15th ed.). Chicago, Illinois: Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc. ISBN 978-1-59339-837-8.

- Shahan, Thomas Joseph (1907). "Antoine d'Abbadie". In Herbermann, Charles George; Pace, Edward A.; Pallen, Condé Bénoist; Shahan, Thomas J.; Wynne, John J. (eds.). The Catholic Encyclopedia: An International Work of Reference on the Constitution, Doctrine, Discipline, and History of the Catholic Church. Vol. I: Aachen–Assize. New York, NY: The Encyclopedia Press, Inc. LCCN 30023167.

- Thorne, John, ed. (1984). "Abbadie, Michel Arnaud d'". Chambers Biographical Dictionary (Revised ed.). Chambers. ISBN 0-550-18022-2.